From Violin to Vin Jaune: How Eleven Madison Park’s Wine Director Rethinks Luxury in the Glass

At three-Michelin-star Eleven Madison Park in Manhattan, the wine list is as storied as the dining room. For Wine Director Adam Waddell, the job isn’t just about curating bottles; it’s about orchestrating emotion, memory and discovery — often in fewer glasses than before.

Waddell, who took over the program in 2025 after joining the restaurant as associate wine director in 2023, did not set out to become a sommelier. He arrived in New York City in 2010 to study classical violin performance, then gradually rewrote his own score.

“I’d played violin since I was four,” he said in an interview. “I came here for music, but at some point I realized I didn’t want to pursue it professionally anymore. I still loved it, but not as a career. Then I had to figure out how to stay in New York and make a living.”

The answer, improbably, turned out to be wine.

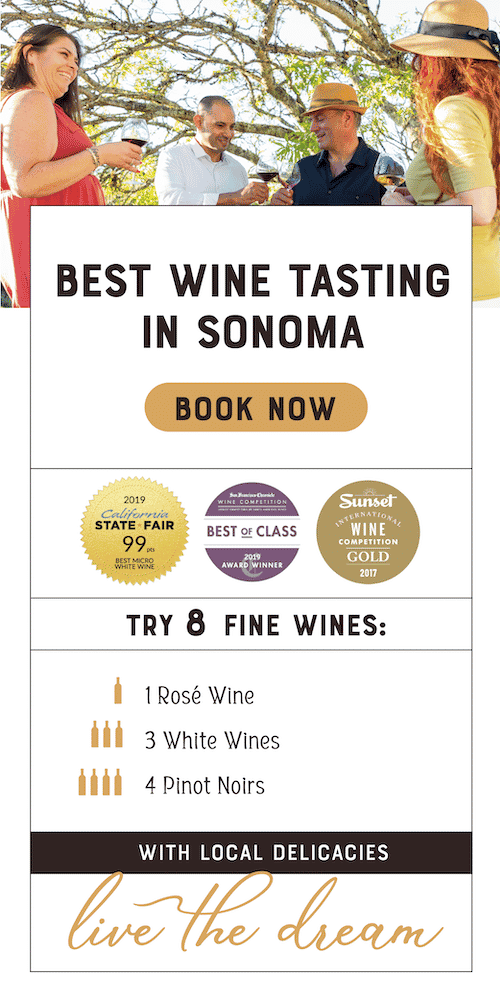

Current Releases from Halleck Vineyard

A Swiss bistro, 21 wines by the glass and one “aha” bottle

Waddell’s conversion story begins in a small Swiss-American bistro called Trestle on Tenth, now closed, where the chef-owner also ran the wine program.

“It was the first restaurant I worked in where there were twenty-one wines by the glass,” Waddell recalled. “We tasted them all before service. He’d tell us what to look for, who the producer was, the region. That’s where I got hooked.”

The program leaned toward European wines—unsurprising given the chef’s Swiss background—and it was there that Waddell first encountered dry Riesling, Jura whites and a range of Italian indigenous varieties. The formative bottle, though, was a 2011 Jacques Puffeney wine from the Jura, a benchmark producer of oxidative, long-aged Savagnin often bottled as Vin Jaune.

“I’d never tasted anything like it,” he said. “Hearing how it was made and then seeing how it tasted—that’s when I thought, ‘I could dedicate my life to this.’”

Mentored early on by his then-chef and by Julia Pope, a wine buyer for an American importer, Waddell went on to earn Court of Master Sommeliers certification, log time on the floors of Jean-Georges, Ai Fiori and Gabriel Kreuther, and eventually become the first head sommelier at SAGA in Lower Manhattan before moving to Eleven Madison Park.

From plant-based dining to “brave” pairings

Eleven Madison Park’s recent history is defined by a bold pivot. In 2021, chef Daniel Humm shifted the flagship tasting menu to a fully plant-based format, a move that drew global attention in the fine-dining world.

Today, the restaurant has reintroduced a handful of animal-protein courses while keeping the core of the menu plant-driven. The idea, Waddell said, was inclusivity rather than retreat.

“We had so many guests say, ‘I love this, but I wish I could share it with someone important to me who doesn’t eat this way,’” he said. “Now there are a few courses where you can choose something that isn’t plant-based, so people with different comfort levels can still have a great experience together.”

The wine program, however, never went fully vegan. The cellar kept its classic Bordeaux and Burgundy—many of them fined with egg whites or casein—and Waddell has focused instead on offering vegan-friendly options by the glass for guests who seek them out.

Philosophically, the list remains rooted in what he calls “classic and tradition,” but the pairings tell a more exploratory story.

“For our standard pairing, the one we pour most often, I want wines that feel like discovery,” he said. “Grape varieties people don’t see every day, regions they haven’t tasted before, producers who are a little more forward-thinking.”

That curiosity extends beyond wine. The shift toward plant-based cuisine, influenced in part by shojin—a Japanese Buddhist temple cooking tradition—opened the door for more sake in the pairings, along with Normandy ciders and other “wine-adjacent” beverages.

“Before the pandemic there was no sake program here,” Waddell said. “Now we can do a beverage pairing, not just a wine pairing. Guests have really embraced that.”

Texture first, flavor second

Ask Waddell how a changing tasting menu affects his thinking and he doesn’t start with aromas or flavors.

“Texture is one of the most important things in pairing,” he said. “When we greet tables, we always ask if there’s anything they don’t like, and people often talk about textures—crunchy, soft, creamy. That tells you how central it is.”

As the kitchen builds a new menu, the team conducts weekly tastings where dishes and potential pairings are evaluated together. Waddell is listening for harmony and friction in the structure of both.

“I’m always thinking about whether the textures line up,” he said. “Do they run in parallel, or are they slightly different in a way that’s pleasant? Do they clash? That’s where a pairing succeeds or fails.”

He’s also aware that expectations at a three-star restaurant cut both ways. Some diners arrive wanting to learn—“odd grapes, ‘weird’ countries,” as he put it. Others come with fixed mental lists of benchmark producers they expect to see on a reserve pairing, even as tariffs and rising prices have made some names difficult to pour by the glass.

“There are guests who know exactly who the top producers are in every region,” he said. “Sometimes they’re disappointed not to see a certain label, but most people are excited to discover something new. They’re here to be stimulated.”

Luxury as story, not volume

If there is a through-line in Waddell’s view of contemporary luxury, it isn’t excess.

“I’ve really noticed that people as a whole are not drinking as much,” he said. “They’re not drinking in quantity like they were before. But they want to drink something unique, something with history or a story that makes the night unforgettable.”

He recalled one couple who previously did the full pairing—roughly a bottle per person—and came back looking for a different kind of evening.

“They ended up ordering a bottle of 1973 ‘Y’ d’Yquem,” he said. “That one bottle became the centerpiece of the night. That’s what they’ll remember.”

For Waddell, that kind of experience—anchored in scarcity, age and narrative rather than sheer volume—is closer to what luxury means today.

California on a New York pedestal

For readers in Sonoma and Napa, the obvious question is how California wine fits into this program, especially in a dining room often associated with Old World classics.

“California is a perfect example of what we mean when we say we’re innovative and forward-thinking,” Waddell said. “It’s not about one grape or one tradition. You can grow almost anything, and people are experimenting constantly. That pioneering spirit fits with how we think about the list.”

On the pairing side, that has meant spotlighting Italian varieties grown in California and pouring aged California wines by the glass, including Joseph Swan Pinot Noir from the Russian River Valley, a historic Sonoma name with deep roots in the region.

“Guests love that wine,” he said. “They’re fascinated that they can have an older Sonoma Pinot by the glass, and we get to tell the Joseph Swan story at the table.”

Beyond Sonoma, he cited producers like Diamond Creek, Colgin, Spottswoode, The Ojai Vineyard and Littorai as mainstays or recent additions that feel aligned with the current menu. Littorai’s experiments with Petit Manseng, a white grape more often associated with Southwest France, are a particular fascination.

“Ted [Lemon] made an incredibly small amount of Petit Manseng,” Waddell said. “To be able to put something like that on the list for a guest who says, ‘I’m in California, show me something a little odd,’ is really exciting.”

Building a cellar for someone else’s future

If the nightly pairings are where Waddell’s curiosity plays out in real time, the purchasing decisions for the cellar involve a longer horizon.

“When I’m buying for the list, I’m thinking about the team that will be here ten years from now,” he said. “Ten years from now, a bottle I bought today will be just hitting its stride at the table. I want them to have the same kind of opportunities we have, and for the program’s trajectory to continue.”

That means continuing to invest in age-worthy wines with proven track records alongside newer regions and styles that may shape the next era of fine dining. The choice to hold both at once leads to the description he eventually found for the “soul” of the list—a question he admitted was difficult to answer.

“It’s classic. We’re rooted in tradition,” he said after a long pause. “But there has to be excitement—some spark. I think the program is brave. We have the classics, and then we have wines that make people say, ‘I did not expect to see that here.’ That sense of bravery and surprise is important to me.”

Mentorship as a measure

For all the talk of Vin Jaune, Petit Manseng and Russian River Pinot Noir, Waddell returns most often to the people around him.

“I feel very privileged to work at Eleven Madison Park,” he said. “Not just because of the cellar, but because of the dedication and passion everyone has for hospitality—from porters and kitchen servers to managers and sommeliers.”

The real joy, he said, isn’t pulling a rare bottle for a table—though that remains a perk. It’s watching the staff he manages and mentors create their own moments of connection.

“Seeing them succeed, seeing them grow, watching them create these memories for guests—that’s the most joyful part of my job.”

For a former violinist, it’s not a bad second act: still working in performance, still playing with timing and tone, only now the instrument is a glass, and the audience participates one sip at a time.